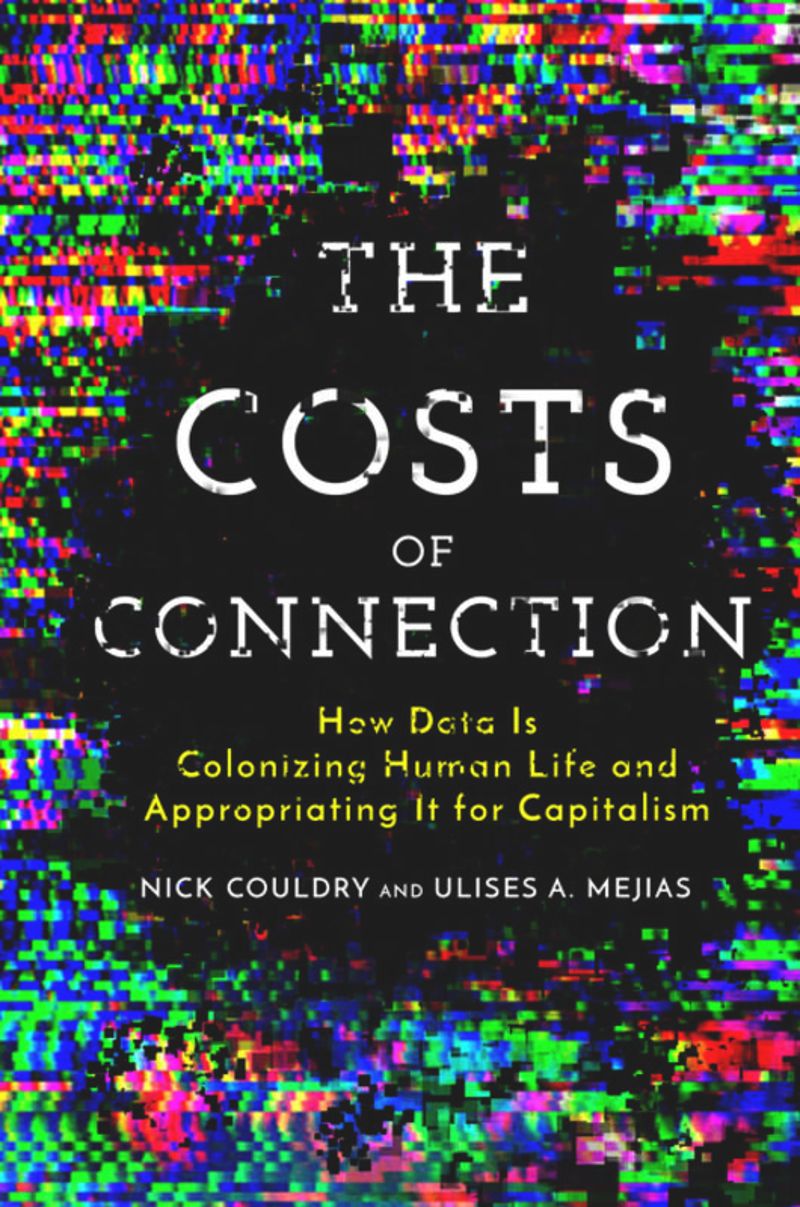

Couldry, N.; Mejias, A. (2019). The costs of connection : how data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. Stanford University Press

Destaques

Rui Alexandre Grácio [2024]

The costs of connection : how data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism, de Nick Couldry e Ulises Mejias, é um livro propositivo que, logo no prefácio, deixa clara a sua tese:

«Human experience, potentially every layer and aspect of it, is becoming the target of profitable extraction. We call this condition colonization by data, and it is a key dimension of how capitalism itself is evolving today» (p. X).

Acrescenta, na sequência, que

«Our argument in this book—that human life is being colonized by data and needs to be decolonized—is no approximation. (…) If historical colonialism annexed territories, their resources, and the bodies that worked on them, data colonialism’s power grab is both simpler and deeper: the capture and control of human life itself through appropriating the data that can be extracted from it for profit» (p. XI).

Por conseguinte, nesta obra é não só estabelecido um paralelo entre o colonialismo tradicional e um novo colonialismo digital, baseado em dados, como este paralelo é inserido na imparável dinâmica do capitalismo que, desta vez, faz do social o seu mercado, e dos dados o novo petróleo. Nesta sua forma, a modalidade é a apropriação da vida humana com vista ao lucro. Com efeito, escrevem os autores,

«the concept of data cannot be separated from two essential elements: the external infrastructure in which it is stored and the profit generation for which it is destined. In short, by data we mean information flows that pass from human life in all its forms to infrastructures for collection and processing. This is the starting point for generating profit from data. In this sense, data abstracts life by converting it into information that can be stored and processed by computers and appropriates life by converting it into value for a third party» (p. XIII).

Mais do que uma tese, trata-se de um alerta, na medida em que para os investigadores,

«The tracking of human subjects that is core to data colonialism is incompatible with the minimal integrity of the self that underlies autonomy and freedom in all their forms» (p. XV).

Todo o livro se desenvolve explanando os processos de apropriação dos humanos pelo mundo digital, mostrando como funciona o «sector de quantificação» fundado em infraestruturas para os quais somos conduzidos crescentemente e que tende a esvaziar qualquer outro tipo de realidade. Esta unidimensionalização da realidade é feita através da datificação e da filosofia que lhe está subjacente: o dataísmo. Este, por sua vez, está ligada a uma uma velha tradição que vê no número, na medida e na matematização a via de acesso à realidade. E, de facto, a cruzada do dataísmo é a de quantificar o qualitativo para desse modo tudo poder codificar e descodificar em termos de dados. Nesta cruzada, é a própria subjetividade que é cada vez mais encurtada e diminuída, ideia que neste livro é referida pelo fazer perigar o espaço mínimo que constitui o si próprio e sem o qual não há autonomia e liberdade. Poderíamos dizer que se trata de uma expropriação da intimidade e da experiência humana enquanto possibilidade de reflexão e de ponderação. Ora é isso que conduz a um estado de imprensar ou de não-pensamento, a que os autores se procuram opor, assinalando-lhes os perigos:

«In this new world, corporations act as colonizers that deploy digital infrastructures of connection to monetize social interactions, and the colonized are relegated to the role of subjects who are driven to use these infrastructures in order to enact their social lives.» (p. 86)

No fundo, trata-se não só de uma reconfiguração do social («redes sociais») como também um esvaziar da autonomia e da liberdade.

Eis um conjunto alargado de passagens significativas.

«But the appropriation of human life in the form of data (the basic move that we call data colonialism) generates a new possibility: without ending its exploitation of labor and its transformation of physical nature, capitalism extends its capacity to exploit life by assimilating new or reconfigured human activities (whether regarded as labor or not) as its direct inputs. (…) This transformation of human life into raw material resonates strongly with the history of exploitation that preceded industrial capitalism—that is, colonialism.» p. XVII)

«More explicitly defined, data colonialism is our term for the extension of a global process of extraction that started under colonialism and continued through industrial capitalism, culminating in today’s new form: instead of natural resources and labor, what is now being appropriated is human life through its conversion into data.» p. XIX

«We can capture the core of our double argument most succinctly by characterizing data colonialism as an unprecedented mutual implication of human life and digital technology for capitalism.» p. XX

«“Human beings are increasingly sensored,” and “sensor data is here to stay. ”Sensors can sense all relevant data at or around the point in space where they are installed. “Sensing” is becoming a general model for knowledge in any domain, for example, in the muchvaunted “smart city.”» p. 8

«Davenport distinguishes three phases in the development of data analytics: whereas early analytics was essentially “descriptive,” collecting companies’ internal data for discrete analysis, the period since 2005 has seen the emergence of the ability to extract value from large unstructured and increasingly diverse external and internal data sets through “predictive” analytics that can find patterns in what appears to have no pattern. Today’s “analytics 3.0” uses large-scale processing power to extract value from vast combinations of data sets, resulting in a “prescriptive analytics” that “embed[s] analytics into every process and employee behavior.” Once the world is seen by capitalism as a domain that can and so must be comprehensively tracked and exploited to ensure more profit, then all life processes that underlie the production process (thinking, acting, consuming, and working in all its dimensions and preconditions) must be fully controlled too.» p. 9

«Another is power over the computing capacity that enables large-scale processing and storage of data, usually known as the cloud, a mystificatory term.» p. 15

«First, there is the ideology of connection itself, which presents as natural the connection of persons, things, and processes via a computer-based infrastructure (the internet) that enables life to be annexed to capital. Connection is, of course, a basic human value, but the requirement to connect here and now—connect to this particular deeply unequal infrastructure—means submission to very particular conditions and terms of power. (…) There is also the ideology of datafication, which insists that every aspect of life must be transmuted into data as the form in which all life becomes useful for capital. Practically, this means not just attachment to a computer connection but the removal of any obstacles to corporate extraction and control of data once that connection is established. The point is not that data itself is bad but that the compulsion to turn every life stream into data flows removes what was once an obstacle to extracting value from those life streams.» p. 18

«Through these various steps, the capacity to order the social world continuously and with maximal efficiency has become, for the first time, a goal for corporate power and state power. Our computers and phones, and even our bodies if they carry trackable devices, become targets of this new form of power.

Two possibilities result that, before digital connection, were literally beyond the imagining of corporations or states. The first is to annex every point in space and every layer of life process to forms of tracking and control. After all, everything is in principle now connected. The second is to transform and influence behavior at every point so that this apparently shocking annexation of life to power comes to seem a natural feature of the social domain.» p. 23

«One key way in which platforms produce the social for capitalism is through a new type of local social relation that stabilizes our habits of connection. Our term for this is data relations.» p. 27

«Today’s data empires are not necessarily interested in land, but they are interested—at least allegorically—in air. If there is one metaphor that captures the structure of this nascent empire, it is that of “the cloud.” Essentially, cloud computing enables on-demand access to a shared pool of computing resources. Because information is stored on third-party servers, not on the owner’s computer, the data is said to live “in the cloud.” More than just a convenient and evocative metaphor, the concept of the cloud operates at different levels to help shape our social realities.» p. 42

«The merciless power of the Cloud Empire comes from an overarching rationality in which data shadows—and eventually stands in for—the very thing it is supposed to measure: life. Apps, platforms, and smart technologies capture and translate our life into data as we play, work, and socialize. AI algorithms then pore over the data to extract information (personal attributes from “likes,” emotions from typing patterns, predictions from past behaviors, and so on) that can be used to sell us our lives back, albeit in commodified form. Science, technology, and human ingenuity are put at the service of this exploitation, making it likely that, unless resisted, the Cloud Empire will in a few decades seem like the natural order of things.» p. 68

«In this chapter, we use the framework of exploring, expanding, exploiting, and exterminating to conduct a transhistorical comparison of dispossession that will reveal continuities between historical colonialism and today’s data colonialism.» (p. 83)

«In this new world, corporations act as colonizers that deploy digital infrastructures of connection to monetize social interactions, and the colonized are relegated to the role of subjects who are driven to use these infrastructures in order to enact their social lives.» (p. 86)

«The transformation of “raw” data into a resource from which corporations can derive value is possible only through a material process of extraction, the second of the concepts we are discussing. As Naomi Klein observes, extractivism implies a “nonreciprocal, dominance-based relationship with the earth” that creates sacrifice zones, “places that, to their extractors, somehow don’t count and therefore can be . . . destroyed, for the supposed greater good of economic progress.” But extraction has also acquired new horizons. Whereas authors like Alberto Acosta use the term neoextractivism to refer to the appropriation of natural resources in neocolonial settings (conducted by authoritarian or even progressive governments stuck in relations of dependency with the Global North), the term can also be used to describe the shift from natural to social resources in the colonial process of dispossession. Today the new sacrifice zone is social life.» p. 90

«Thus, extermination in data colonialism is better understood not as the elimination of entire peoples but as the gradual elimination of social spaces that can exist outside data relations. We know from looking at the legacy of historical colonialism that genocide always entailed the obliteration of cultures, languages, and ways of life. In that sense, data colonialism continues mass media’s project of homogenization, a project whereby difference is subdued in the interest of conformity. The actual extermination of subjects becomes unnecessary once the elimination of forms of life that do not exist merely as inputs for capitalism is achieved.» p. 107

«Although not exactly narcotics, some of the products generated by the Cloud Empire are notorious for their addictive and exploitative nature.» p. 109

«As Hacking writes, “Normality” emerged “to close the gap between ‘is’ and ‘ought.’”» P. 121

«At the most basic level, what is missing is consent. As Julie Cohen puts it, consent to the terms of data collection is somehow “sublimated . . . into the coded environment.” In addition to consent, choice also gets subsumed by “Big Data’s decision-guidance techniques.” And if consent and choice are bypassed, so too implicitly is the person with a voice whose reflections might have contributed to our understanding of the social world. With so much discriminatory processing controlling how the world even appears to each of us, this new social knowledge gives human actors few opportunities to exercise choice about the choices offered to them. There is something disturbing about this for human freedom and autonomy and for the human life environment that is being built here.» p. 129

«Marketers describe this personalization as “one-to-one communication” and “one-to-one dialogue.” Yet there is nothing dialogic about the individual’s emerging relation to capitalism or the continuous caching of social life on which it relies.» p. 133

«Biological evidence is presented to show that economics’ concept of preference (the rational actor making choices in the market) must be disaggregated into “the output of a neural choice process.” Biology here means brain imaging.» p. 141

«It is a curious irony that B. J. Fogg, a leading developer of unconscious behavioral influence through online choice architectures, named his new science of intervention “captology.” Knowledge by capture, influence by appropriation.» p. 150

«Data colonialism’s new social knowledge generates a deep form of injustice in the very construction of the social and political domain. Philosopher Nancy Fraser calls this sort of problem “meta-political injustice”: justice in who or what counts as someone to whom or something to which questions of justice apply at all. One way to open up these issues is ethics. As Tristan Harris, one of Fogg’s former students and a founder of the Truth About Tech campaign in the United States, asked, “What responsibility comes with the ability to influence the psychology of a billion people? Where’s the Hippocratic oath?” As yet, we simply don’t know.

But ethics must start out from an understanding of the self. What if the boundaries of the self too are under sustained attack by data colonialism? If so, we may require philosophical resources to identify with precision the violence that data colonialism does to the self and, by extension, the social world as well.» p. 151

«The reason both traditional surveillance and datafied tracking conflict with notions of freedom derives from something common to both: their invasion of the basic space of the self on behalf of an external power.» p. 155

«The self’s minimal integrity is the boundedness that constitutes a self as a self. Often that boundedness is experienced in defending a minimal space of physical control around the body, but it can also be invaded without physical incursion—for example, by acts of power that intimidate, shame, harass, and monitor the self. By “the space of the self” we mean the materially grounded domain of possibility that the self has as its horizon of action and imagination. The space of the self can be understood as the open space in which any given individual experiences, reflects, and prepares to settle on her course of action.» p. 158

«By salvaging the concept of the minimal integrity of human life—the bare reality of the self as a self—we identify something that we cannot trade without endangering something essential to ourselves. This “something” underlies all the formulations of privacy and autonomy from culture to culture and period to period.» p. 159

«By installing automated surveillance into the space of the self, we risk losing the very thing—the open-ended space in which we continuously monitor and transform ourselves over time—that constitutes us as selves at all.» p. 161

«Two points are crucial: first, that these goods are and must be “exclusive”; and second, that this right to exclusivity is “inalienable”: it cannot be given up without giving up on the self as such.» p. 167

«(…) autonomy itself is being reconfigured by capitalist data practices.» p.. 168

«There is a link here to the wider value of “sharing” in contemporary culture. As Nicholas John points out, what is most striking about sharing as a metaphor is the extendibility of what is to be shared: from thoughts and pictures to information sources and life histories to everything and anything. Sharing our lives has come to imply a broader value of “openness and mutuality” but at the risk of mystifying the communities we supposedly form online. In a world in which we are constantly induced to share personal information, data collection becomes part of a social life within which, somewhere, we assume that autonomous subjects still exist.» p. 169

«There was something deeply paradoxical in the proposal of a marketer of body sensors at the Digital Health Summit in January 2014: “Our cars have dashboards, our homes have thermostats—why don’t we have that for our own bodies?” Natasha Dow Schüll’s comment is acerbic: “Instead of aspiring to autonomy, they wish to outsource the labor of self-regulation to personal sensor technology.” The attempt at self-regulation (or selflegislation, as Kant and Hegel called it) is basic to what a self is and so cannot be delegated to algorithms without giving up on the basic fabric of the self.» pp. 171-172

«The risk is clear, however: that since we have no choice but to go on acting in a world that undermines the self’s autonomy, one consequence is that we may progressively unlearn the norms associated with it. As the second quotation at the beginning of the chapter head suggests, data colonialism’s subjects may come to unlearn freedom in time.» p. 173

«Data colonialism works to dismantle the basic integrity of the self, dissolving the boundaries that enable the self to be a self. It is the self in this bare sense that must be salvaged from data colonialism, using all available legal, political, and philosophical means.

This makes the stakes of our argument very clear. None of the ideals desired in today’s societies—their democratic status, their freedom, their health, or otherwise—make any sense without reference to an autonomous self in the minimal sense defended in this chapter.» p. 184

«We argued that underlying these was something even more fundamental: the drive to capitalize human life itself in all its aspects and build through this a new social and economic order that installs capitalist management as the privileged mode for governing every aspect of life. Put another way, and updating Marx for the Big Data age, human life becomes a direct factor in capitalist production. This annexation of human capital is what links data colonialism to the further expansion of capitalism. This is the fundamental cost of connection, and it is a cost being paid all over the world, in societies in which connection is increasingly imposed as the basis for participating in everyday life. The resulting order has important similarities whether we are discussing the United States, China, Europe, or Latin America. The drive toward this order is sustained by key ideologies, including the ideologies of connection, datafication, personalization, and dataism.» p. 189

«To sum up, the problem and challenge of contemporary data practices is neither data nor simply the particular platforms that have emerged to exploit data. The problem is the interlocking combination of six forces, unpacked in the previous chapters: an infrastructure for data extraction (technological, still expanding); an order (social, still emerging) that binds humans into that infrastructure; a system (economic) built on that infrastructure and order; a model of governance (social) that benefits from that infrastructure, order, and system and works to bind humans ever further into them; a rationality (practical) that makes sense of each of the other levels; and finally, a new model of knowledge that redefines the world as one in which these forces together encompass all there is to be known of human life. Data, in short, is the new means to remake the world in capital’s image.» pp. 191-102

«A vision that rejects a rationality that claims to bind all subjects into a universal grid of monitoring and categorization and instead views information and data as a resource whose value can be sustained only if locally negotiated, managed, and controlled.» p. 196

«Capitalism has always sought to reject limits to its expansion, such as national boundaries. But now, as not only human geography and physical nature but also human experience are being annexed to capital, we reach the first period in history when soon there will be no domains of life left that remain unannexed by capital. And yet this seemingly inevitable order has a fundamental flaw from the perspective of human subjects. That flaw is its incompatibility with a different kind of necessity, the most basic component of freedom, which we call the minimal integrity of the self. The emerging colonialist and capitalist order is therefore, under whatever disguise it operates, incompatible with every political structure built on freedom, including democracy in all its forms, liberal or otherwise.» pp. 196-197

«How does this vision start? It begins by rejecting in principle the premises of the new social and economic order and, for example, insisting at every opportunity that corporations—indeed all actors—who use data can do so legitimately only if that broad usage is based on respect for the human subjects to whom that data refers and for the goals and awareness of those data subjects.» p. 197

«Indeed, dataism claims to find a higher force than human life, the force of information processing or algorithmic power, which appears to know human life better than life can know itself. But this ideology clashes with a much older vision of how human life should be, an ecological view of human life, unchallenged until very recently, which assumes that human life, like all life—whatever its limits, constraints, and deficits—is a zone of open-ended connection and growth. This view of human life understands life (my life, your life, the life of the society we inhabit) as something that finds its own limits as it continuously changes and develops, even as forms of human power seek to manage and control it.» p. 199

«At this point, two questions—about social/political order and rationality—risk becoming knotted together. We must disentangle them.

The answer cannot be to reject order. Human life, like all life, is sustainable only on the basis of a certain degree of order that conforms to the physical and psychic needs of human beings. Whereas the word order has acquired certain negative connotations within the ambit of Western rationality, as something implying imposed structures, it can also mean “balance,” as in harmony, and beneficial forms of interconnectedness and living well together. Order is the abstract term for many elements of human life we are truly thankful for: routine, expectation, the security of knowing that people generally act as they say they will. But one must always ask: Order for whom? Order on what terms?» p. 201

«The method and goal, then, is not to abandon the idea of rationality (or order) but to reanimate it in terms of different values. What is needed is an “epistemological decolonization” that “clear[s] the way for . . . an interchange of experiences and meanings, as the basis of another rationality which may legitimately pretend to some universality.” The goal is not to abandon rationality, order, or even the claim to universality but to reject the highly distinctive claim to absolute universality that characterizes European modernity.

We reach here the core of what is wrong with data colonialism’s order: its vision of totality. Connection—a potential human good in itself—is always offered today on terms that require acceptance of a totality, a submission to a universal order of connectivity. Data colonialism is, after all, not the only vision of human order—indeed, of the human uses of data— that is possible. But its way of “covering” the world—of compelling us to believe there is no other way to imagine the world unfolding and becoming known to us—is part of its power and its danger. Data colonialism provides a “horizon of totality” (in Enrique Dussel’s useful phrase) that it is difficult but essential to resist and dismantle.

We must hold on to a different vision of order. An order that understands humanity in a nontotalizing way, that rejects the equation of totality with sameness and the imposition of one reading of how the world and its knowledges should be organized.» pp. 202-203

«It is to articulate a vision that, against the background of Big Data reasoning, will appear counterintuitive to many, a vision that rejects the idea that the continuous collection of data from human beings is a rational way of organizing human life. From this perspective, the results of data processing are less a natural form of individual and societal self-knowledge than they are a commercially motivated “fi x” that serves deep and partial interests that as such should be rejected and resisted.

It may help here to listen to those who have fought for centuries against capitalism and its colonial guises. Leanne Betasamosake Simpson reflects on rationality but from the perspective of human meaning. She affirms a meaning that “is derived not through content or data or even theory . . . but through a compassionate web of interdependent relationships that are different and valuable because of difference.” Why difference exactly? Because only by respecting difference do we stand any chance of not “interfer[ing] with other beings’ life pathways” and their possibilities for autonomy.36» pp. 203-204

«This, incidentally, is what distinguishes the universalizing involved in our argument from the universalizing that colonialisms have helped shape, indeed, the universalizing that underlies the whole vision of Big Data.» p. 208

«Those who formulate critiques, such as the ones contained in this book, are often asked how to solve the problems they have identified. Although solutions to problems that have taken centuries to unfold must necessarily be partial, incomplete, and tentative, this is indeed our most concrete proposal: that anyone who feels dispossessed by the Cloud Empire should have opportunities and spaces to participate in collective research about the shared problems that data now poses for humanity.» p. 210

Última atualização em 30 de novembro de 2025